Dr Gill Harrop

If you use social media, the chances are that you’ve seen the ‘man vs bear’ question being posed, discussed and even argued about. Essentially the question is this:

“If you’re walking through a forest, would you rather encounter an unknown man or a bear?”

Tiktokker ScreenshotHQ posted a video showing women answering this question and an overwhelming majority said they’d choose the bear. By May 2024, this video had been viewed more than 17 million times and provoked a plethora of responses. Most could be split into three categories: (1) women explaining why they’d choose the bear, (2) some men being incredulous and/or angry that women chose the bear, and (3) people noting that those who don’t understand women choosing the bear perhaps don’t understand the harassment and risk that many women face on a daily basis. By exploring these responses, we can start to understand the psychology behind them.

Why women choose the bear

The first thing to note is that this is not actually about bears. It’s not a debate on brown bears versus black bears or how to survive a bear attack. It’s a hypothetical situation that shines a light on the harassment that many women experience in the world, and the everyday decisions that many women have to make to stay safe. So why are women choosing the bear? There are two main options here: either women really love bears, or they’re seeing the unknown man as a greater potential risk. Assuming it’s the latter, is this a reasonable concern for women to have? Unfortunately, the data suggests it is. The World Health Organisation (2018) found that around 1 in 3 women have been subjected to physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence and EVAW (2022) reported that 2 out of 3 women aged 16-34 had experienced harassment in a single 12-month period, 44% had experienced catcalls, whistles and unwanted sexual comments and 29% had experienced being followed. The number of sexual offences, including rapes, reported to police in England and Wales is at an all-time high and around 2 women a week are still being killed by a partner or ex-partner, a figure that incredibly, has stayed the same for decades. Against this backdrop, we see the devastating murders of women such as Sarah Everard, Zara Aleena and Sabina Nessa, who were attacked and killed by men while walking home or to meet friends. It’s important to note of course, that it’s not all men. It’s not even most men. The problem is that when faced with an unknown man, there’s often no way for women to tell if he’s dangerous or one of the many good ones. The dangerous ones don’t wear badges or villain costumes to reveal their true nature, so women can know how to react. Wayne Couzens even wore a police uniform, and had a warrant card, which should have been the ultimate signal that he could be trusted, that he was safe, and yet he still abducted and killed Sarah Everard just because he wanted to. So the man versus bear decision becomes a question of risk assessment.

Additionally, many women spoke about choosing the bear as they would be believed more readily if they reported that the bear had attacked them rather than the man. X user AmberLynnfit_noted that if a woman survived a bear attack, no one would ask what she had been wearing or been drinking. No one would suggest that the bear had always seemed really nice beforehand and that she might have ‘led him on’ or encouraged the attack. They wouldn’t have checked to make sure she had really said no and they certainly wouldn’t suggest not reporting the bear, for fear of ruining his reputation. While this response is arguably somewhat tongue-in-cheek, research on victim blaming confirms that these are very real concerns for women and girls who experience male violence. Anderson and Overby (2020) explored the negative impact of victim blaming on survivors of sexual violence and found that victim-blaming responses were common amongst friends and family, even when they supported the victim e.g. asking what they were wearing or if they had done anything to lead the perpetrator on. Anderson and Overby found that such victim blaming negatively affects the way that people respond to survivors of violence and can make it more difficult for victims to report their experiences.

Why does victim blaming happen at all?

Lerner (1980) suggested that people try to make sense of what we see around us to fit in with the idea that the world is just, everything happens for a reason and we will be okay as long as we just follow the ‘rules’. Essentially, bad things only happen to people who don’t follow the rules so as long as we follow them, then we’ll be okay. Of course, this is not how the world actually works and the problem occurs when this belief in a just world is used to frame people’s experiences of violence or harassment. When we see that someone else had a bad experience, the just world hypothesis can lead to us feeling scared that it might happen to us and make us worry that we are also at risk. So to make ourselves feel better and safer in what can feel like quite a scary world, we can seek to identify something the victim did that might have led to the dangerous situation happening. For example, if someone learns that the victim had a few drinks before an assault, they might say to themselves “well I wouldn’t drink that much so I’ll be okay”. Or they might decide that the victim said or did something that led the perpetrator to behave violently, so they can think “I would never behave that way, so I don’t need to worry”. The problem is that in making themselves feel better and more safe, they are unfairly placing blame for what happened onto the victim. Stromwall, Alfredsson and Landstrom (2023) found that belief in a just world was a powerful predictor of how much blame was attributed to victims of sexual violence. Essentially, the more we want to believe the world is fair and we can keep ourselves safe, the more likely we are to engage in victim blaming.

So how can we prevent victim blaming?

Firstly, by recognising that the only person responsible for violence, abuse and harassment is the perpetrator. It doesn’t matter what someone was wearing, what they were drinking, or whether they had been ‘nice’ to the person prior to the event. 100% of the responsibility lies with the perpetrator, so the next time someone describes a difficult situation to you or discloses that they have experienced harassment, consciously try to replace victim-blaming questions with more supportive responses such as ‘that’s not okay’, ‘it’s not your fault’ and ‘what can I do to help?

Why are some men angry that women choose the bear?

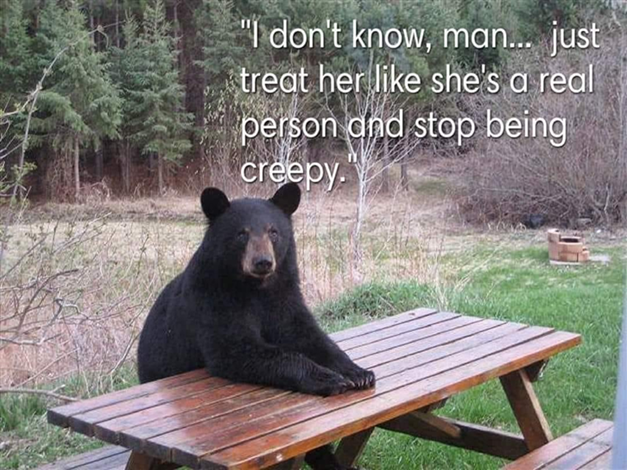

Much of the answer to this comes down to perception. Those who are annoyed at women choosing the bear often perceive it as a dig at them or at men in general. As if the women are saying “I’d rather risk death or injury from a dangerous animal than encounter you”. But as discussed above, the scenario is based on an unknown man. Women are not saying they’d choose a bear over their partner, their dad or their male friends, who they know to be trustworthy. They’re rejecting the unknown male, where there is no way of knowing the level of risk posed. This response also speaks to some people’s lack of understanding of the risks that women face in everyday life and perhaps even an unwillingness to accept that these are women’s experiences. They assume that women must be exaggerating the risk or must just be a man-hater. Why else would they choose a dangerous bear over a ‘safe’ man? They don’t perceive the man as a risk to them so can’t understand why a woman might view it differently. The reality of course is that men getting visibly angry at women choosing the bear, and berating them for their decision, actually reinforces many women’s response to the question. As X user AndreaRhoden put it “a bear wouldn’t ask me ‘man or bear’ and then ‘bearsplain’ to me why I chose wrong’. If someone get genuinely angry at women for choosing a hypothetical bear in a hypothetical scenario, and just wants to tell her why she’s wrong, rather than listening to and believing her lived experience, maybe they would benefit from engaging in some self-reflection about how to better support the women in their life.

So what can you do?

Consider what good allyship looks like, think about how to be an active bystander and listen to a range of opinions on this hypothetical scenario. A great place to start is Tiktokker DadChats who brilliantly analyses the scenario from a statistical perspective to determine the risk of the man versus the bear. You can also talk about it to others. Fairbairn (2020) suggests that having conversations about hypothetical scenarios is an ideal way for people to get a better understanding of violence against women and girls, and see the role that they can play in tackling it. Such conversations lead to narrative shifts and development of a better understanding of the societal norms that enable, or conversely tackle, such violence and harassment. If we’re going to tackle violence against women and girls, more people have to first acknowledge that there is a real problem which is worthy of tackling, and having these conversations is a vital part of that process.

How would you answer the man versus bear question now?

Maybe you’re still strongly team bear, or maybe you’re dead set on choosing the man and think that it’s ridiculous that anyone would choose the bear. Whichever way you fall on this issue, here’s the reality: most women ARE choosing the bear. Whether you consider that to be a sensible choice or not, this is not coming out of nowhere and it is too many women to just brush it off as silly decision-making, extreme feminism or even a lack of bear-knowledge. If you’re lucky, you didn’t have to be told about self-defence from a young age, or learn to ‘wolverine’ your keys through your fingers while walking home at night to fight off a potential attacker. Hopefully you’ve never experienced having to get off a train at the wrong stop as the creepy guy in the carriage won’t leave you alone, been groped in a pub/coffee shop/on the street, had to cross the street to get away from the man who was following you or called out to a pretend housemate as you opened your front door so the taxi driver who had been making lewd comments to you the whole way home thought there was a man inside your house. If you’ve never had to think about any of these things, the bear probably does seem like a crazy choice. But that is the reality for many women as they go about their lives and until that changes… sorry, but I’m choosing the bear.

Dr Gillian Harrop

Dr Gill Harrop is a Senior Lecturer in Forensic Psychology at the University of Worcester and leads the UW Bystander Intervention Programme. She is a member of the Trauma & Violence Prevention research theme within the Interpersonal Relationships and Wellbeing Research Group.