by Dr Pamela F Murray, Worcester Business School

The People and Work Research theme brings together researchers with an interest in understanding the dynamics of workplace relationships from an interpersonal and organisational perspective. A major focus of this work involves developing approaches to enhance leadership and the work-based practice of existing and future employees.

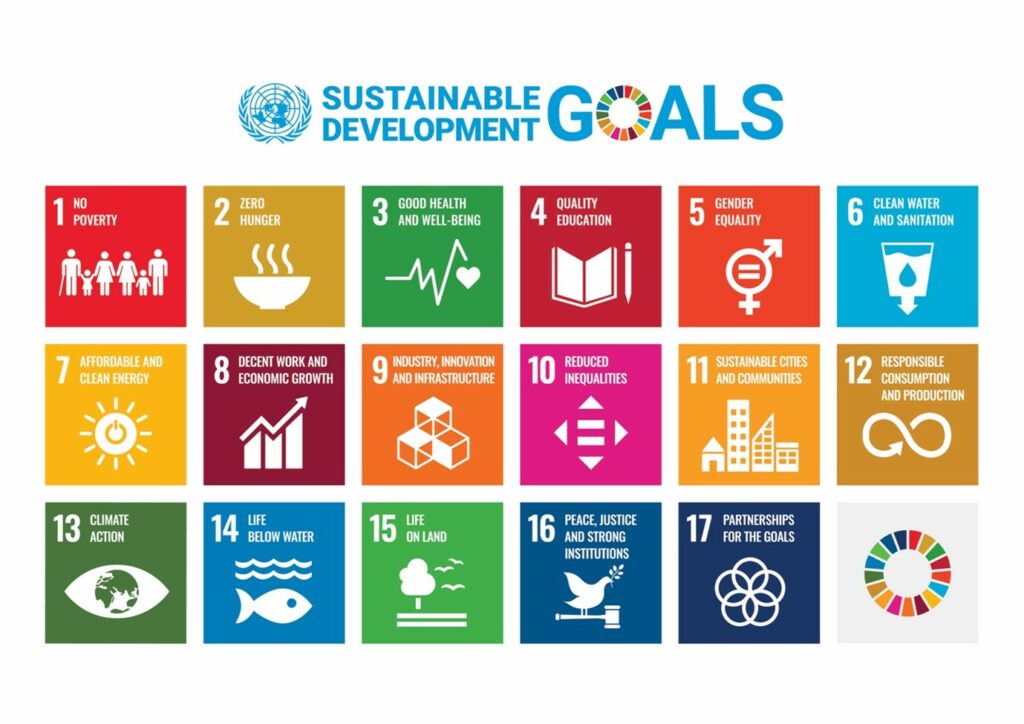

In the role of Leadership Development Facilitator for the Careers and Employability Service Platinum Leadership Award, I collaborated with Rose Watson from the University of Worcester Careers & Employability Service, combining forces to produce a rewarding experiential learning experience fuelled by a clear purpose, to be of service to others. Therein I sought to develop a programme for students that would align with the United Nations Principles for Responsible Management Education (PRME). PRME’s mission is to transform management education and develop responsible decision-makers of tomorrow to advance sustainable development. It engages business and management schools to ensure they provide future leaders with the skills needed to balance economic, environmental, and social goals, while drawing attention to the UNs Sustainable Development Goals.

The Platinum Leadership award directly mapped to:

SDG4 Quality Education: Ensure inclusive and equitable education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all.

SDG16 Peace, Justice & Strong Institutions: Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels.

SDG 17 Partnerships for the Goals : Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the global partnership for sustainable development.

What happened on the Platinum Leadership Worcester Award?

Twelve highly motivated students were invited to take part in the Platinum Award. These students had already progressed through preceding bronze, silver and gold award levels of the scheme, and had demonstrated that they were able to competently apply knowledge and skills in employment settings. Rolled out over a period of three days, the aim of the platinum programme was for students to take the lead on developing strategies to promote a sense of belonging in their fellow peers to underpin student confidence and encourage cohesion.

First and second day activities blended theory and its implementation. From the off students explored their self-awareness and self-regulation using a range of salient diagnostics to prepare them for the ensuing development scenarios. For the immersive aspects of the learning experience, a ‘challenge by choice’ philosophy was accompanied by the reality that leaders can be ‘visible and vulnerable’.

Situational tasks called for solution-based learning to evaluate plausible alternatives. Through a newly developed leadership-oriented lens, discussions were lively! Approaches were tried out to address and resolve concerns, including the ‘coming alongside’ technique intended to garner accurate empathy of benefit to the overall process. With practise and feedback, participants generated and maintained encouragement to fulfil their goals.

Our ‘leaders-under-training’ became mutually accountable for accomplishment. Progressing from group work to teamwork, they displayed an awareness of how to use dynamics to get the best from one another, drawing on emotional maturity to prevent derailment of the project work and ensure its success.

From the gains elicited from the application and reflection activities in the guided discovery, the third day involved a formal presentation of proposals to key parties interested in supporting student belonging.

My reflections as a facilitator of the award

I appreciated the chance to share an introduction to sustainable leadership proficiency and ethical literacy for the enrichment of others. It was rewarding to witness the development of the Platinum Awardees’ leadership identities, expressed through values in action, bespoke signature strengths, and resilience. The Platinum Leaders demonstrated their capabilities of worth to their local and wider communities, whilst expanding their skill portfolios.

The student perspective on becoming a Platinum leader

Oliver Nightingale, Physiotherapy Student, Department of Allied Health

What did you take away from the experience?

“The 3-day leadership award opened my eyes to the impact of leadership and team cohesion. The lessons, experiences and skillset obtained from the leadership course have and will continue to support and sustain my development as a current student and future professional practitioner. The collaborative aspect of the course stands out as an impactful and valuable experience. Despite multidisciplinary working being a common occurrence in healthcare, the breadth and diversity of students on the course enabled me to seek out different perspectives, viewpoints and experiences that shaped our cohesive collaboration on the day. The activities on the leadership course deepened my understanding of team cohesion, resilience, advocating for others, problem solving, courageous leadership and networking.”

How will you use your leadership skills in the future?

“I have been involved with the Children’s Alliance, volunteering to play a small role in the facilitating of the conference. I have gone on to become the Department Rep for Allied Health, being the student voice representative for over 500 students and planning multi-disciplinary conference within the school. I have also been inspired by the potential of effective leadership, innovation, and sustainability, and I am planning to develop my own charity to provide more accessible care to those in society with limited access and vulnerabilities, such as young people and individuals living with disabilities.”

“The Platinum Award was an incredible catalyst to help me realise my potential, showing the importance of a ‘can do’ attitude, empathy, grit, kindness and courage to work with others to make real change.”

For further information and to find out more about Pamela’s work, please get in touch p.murray@worc.ac.uk.

Dr Pamela F Murray

Dr Pamela F Murray Senior is a Lecturer in Leadership and Organisational Behaviour Worcester Business School, and a member of the University of Worcester Interpersonal Relationships and Wellbeing Research Group, People and Work research theme. In this post, Pamela discusses her work in leadership learning and the success of the Platinum Leadership award, developed in partnership with the University’s Careers and Employability Service.